How, as historians, can we facilitate a physical understanding of the world in which we live, and how it has been formed throughout it’s existence as well as from our own? All human endeavors exist on a dual plane of time and space, and at each moment we are wrapped up in the cosmological game of survival that bleeds forth from the essence of a world in action. Historians, who are interested in the study of man’s experience in time and space, must also, as W. Gordon East reveals, be engaged in discussing the “problems of location.” (East, 1967, p.10) One way to understand these problems is through the incorporation of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) as a tool to answer the question posed by the researcher. A GIS, as J. Scurry writes, is

“a computerized data management system used to capture, store, manage, retrieve, analyze, and display spatial information. […] GIS differs from other graphics systems in several respects. […] data are georeferenced to the coordinates of a particular projection system. This allows precise placement of features on the earth’s surface and maintains the spatial relationships between mapped features. As a result, commonly referenced data can be overlaid to determine relationships between data elements.” (What is GIS?)

In this post, I will show how questions can be answered through the adoption of GIS as a methodological tool for the advancement of historical understanding. To do this, I will begin by setting up the world in history, in a spatial, temporal, and humanitarian context. I will then briefly examine two approaches to history, quantitative history and by looking at Fernand Braudel from the Annales, that have aided in addressing the need for a geographical understanding of history, as well as how these schools can benefit from the use of GIS services. In the last section, where I intend the focus of this post to be, I will show how GIS can be incorporated as a historical approach. To accomplish this I will provide the reader with an understanding of GIS, provide an overview of GIS scholarship, discuss the importance of data to GIS, and close by providing a sampling of scholarly incorporations of GIS as a historical enhancement tool. So, why learn about GIS as a historical tool? Because as humanists, “we are drawn to issues of meaning, and space offers a way to understand fundamentally how we order our world.” (Bodenhamer, 2010, p.14)

The World In History

There are three major avenues for research in historical GIS work. These are the spatial, the temporal, and the humanitarian. Though each of these avenues are distinctive, an analysis of them does not happen in isolation and as we read through them the reader will find many overlapping themes. We will also be coming back to these themes throughout the entirety of the paper because each of them enhances our understanding of the historical world and the realities therein.

Spatial

The spatial world is the material construct of the world around us. It is made up of shapes, colors, depth, and a myriad number of objects[1]. (Couclelis, 1992) Throughout history there have been numerous ontological frameworks for how we view the world around us. These frameworks help to explain man’s conception of the world he lives in. Predominating outlooks have changed throughout history, but the world in which these outlooks have taken place is metaphysically the same. The physical world provides us with obvious natural boundaries which have had a significant impact on how we have interacted upon it. W. Gordon East, writing in 1967, writes that

“The best frontiers of separation, especially in the past, were afforded by the oceans, the deserts, mountain systems, marshy tracts, and forests, for the good reasons that such areas set obstacles to human movement and could not support a dense population.” (East, p.100)

Even though these boundaries create boundaries of protection, “the physical environment remains a veritable Pandora’s box, ever ready to burst open and to scatter its noxious contents.” (East, p.1) For all of man’s attempts to subjugate the earth, the earth has a way of bringing us back into awareness of our own existence.

Two major distinctions in worldview are between the Ptolemaic view and the Copernican view, which battled over the location of the earth in the universe. Speaking about the Medieval understanding of the Ptolemaic view of the world, Lovejoy writes “The world had a clear intelligible unity of structure, and not only definite shape, but what was deemed at once the simplest and most perfect shape, as had all the bodies composing it. It had no loose ends, no irregularities of outline.” (Lovejoy, 1960, p.101) Later on Lovejoy states that “It is sufficiently evident from such passages that the geocentric cosmography served rather for man’s humiliation than for his exaltation, and that Copernicanism was opposed partly on the ground that it assigned too dignified and lofty a position to his dwelling place.” (Lovejoy, p.102)

Another model of viewing the world involves land ownership, and the definitional arguments over property. Couclelis, speaking on the predominating view of space in relation to the Western tradition, informs us that

“Western culture is apparently unique in its treatment of land as property, as commodity capable of being bought, subdivided, exchanged, and sold at the market place. It is at this lowest level of real estate (from the Latin res, meaning thing), that we find the cultural grounding of the notion of space as object. Further up the hierarchy, at the level of countries, states, or nations, precise boundaries are needed again to determine what belongs to whom, who controls whom and what, and for what purpose.” (Couclelis, p.67)

Couclelis then goes on to inform her readers of six reasons why human territories often elude spatial analysis. These reasons are: there is a constant effort to establish and maintain; they are defined by a nexus of social relations rather than by intrinsic object properties; their internal structure changes not through movement of anything physical, but through changes in social rules and ideas; they do not partition space, although they may share it; their intensity at any time varies from place to place; and finally, they are context and place specific. (Couclelis, p.68)

Geographical space, in many respects, is fluid. The arbitrary lines that are drawn upon it by man have little meaning on the land as an entity to itself. Waldo Tobler, speaking in 1970, invoked the “First Law of Geography” by stating that “everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things.” (1970) What this means in relation to the geographical conception of space is that it is easier to relate events that take place in a close proximity to one another as opposed to those that take place far away from one another. Couclelis tells us how we should conceptualize our sense of space as being in territorial relationships by stating that

“It is as if landmarks, places, and other geographic entities were defined in neither an absolute nor a relative, but in a relational space, where object identity itself is at least in part a function of the nexus of contextual relations with other objects.” (Couclelis, p.74)

By looking at Tobler’s Law and Couclelis’ “relational space” we see the need for having a conception of transitional changes of movement in our ontological framework.

Though it changes shape, moves around, acts and is acted upon, the land is always with us, and, as such, it “provides a common denominator to all historical periods.[2]” (East, p.8) While we are able to stand upon the space we inhabit, we are not able to remain there indefinitely[3]. In traditional Western thought we conceptualize time along a linear model always moving on towards infinity, but we can only think of “the Earth’s surface [as] fundamentally finite.[4]” (Gregory, 2010, p.61)

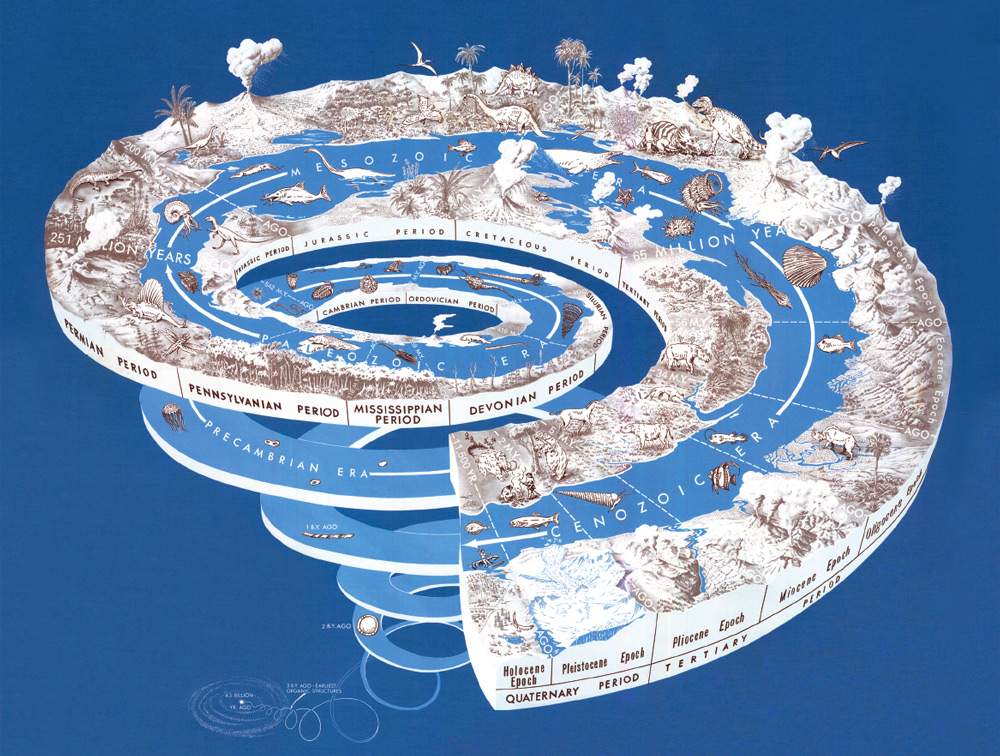

Temporal

On the other side of the space token is the notion of time; the two cannot be separated.[5] (Gregory, p.61) Ian Gregory informs us of the six ways of conceptualizing time (Gregory, p.60) including: linearly, calendary, cyclically, containerly, branching, and multiple perspectives. In a GIS environment, it would seem that the easiest way to view historical spatial changes over time would be highest by using a linear model. Corrigan writes that

“The display of change over time that is observable in such a GIS, especially when presented as an animation, can disclose much about the way in which people and culture move through space, appear and disappear, and exist in relation to natural environments.” (Corrigan, 2010, p.81)

Many of the historical GIS applications that I have seen, and some I will touch on in a later section, have such a linear time tool as a way to view the historical analysis.

History is the subject that “locates us in time,[6]” (Ayers, 2010, p.5-6) and if we relook at Tobler’s law about geography and relate it to time we will see that nearer periods of history are more similar than distant periods of history. As historians we are often prone to large groupings of historical periods such as saying, medieval or roman, but when we dig down deep into the transitionary periods of time it is difficult to see where one period ends and another begins.

Humanitarian

The human experience in, and upon, the world is primarily what the field of history is concerned with and looking at how we have been formed by our past, and in this context, humanity has been forced to understand nature and make adjustments.(East, p.2) There are a plethora of articles that discuss how man has had a strong influence upon the world in which we live. It is man that provides meaning to place by establishing it as an object. Robert David Sack writes that

“Space and time are fundamental components of human experience. They are not merely naively given facets of geographic reality, but are transformed by, and affect, people and their relationships to one another. Territoriality, as the basic geographic expression of influence and power, provides an essential link between society, space, and time. Territoriality is the backcloth of geographical context- it is the device through which people construct and maintain spatial organizations. For humans, territoriality is not an instinct or drive, but rather a complex strategy to affect, influence, and control access to people, things, and relationships.” (Sack, 1986, p.216)

This is how places, as objects of study, are created. The human conception of place also has a reliance on the area around it.[7] (East, p.28)

There is a famous adage from Shakespeare’s As You Like It which states “All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players; They have their exits and their entrances, And one man in his time plays many parts,” (Act 2, Scene 7, p.83) but, unlike in a theatrical performance, “history…is not rehearsed before enactment, and so different and so changeful are its manifestations that it certainly lacks all unity of place, time, and action.” (East, p.2) So how do we make sense of humanity’s entrances and exits, and relations with one another and the world itself? Couclelis informs us that “the key is to be sought in human cognition, in learning from how people actually experience and deal with the geographic world.” (Couclelis, p.66)

Quantitative History & One Annales Approach

There are two separate approaches to history that are relevant to a GIS approach that I would like to take a moment to discuss. The first is a quantitative history which relies on statistical data to examine historical questions. The second is by looking at on work by Fernand Braudel from the Annales.

Quantitative History

The value of a GIS methodological approach to answering a quantitative historical question comes precisely because that is what each of them do. The whole concept of quantitative history, and it’s significance to this post, is that it was one of the beginning methodologies that began to make a “reliance on numerical data.” (Green & Troup, 1999, p.141) Though numerical data in and of itself is not useful for a GIS project, if it can be georeferenced, then the historian can begin to gain a greater appreciation for the data and it’s relation to the human experience in the world. For instance, U.S. Census data conveys a lot of information, and all of this data comes from particular regions, territories, and places. This information, collected decennially, provides many historians with the information that they need to track historical trends and patterns. This type of data has allowed for historians to focus their “minds on specific historical problems and on ways in which [they] as historians construct [their] material.[8]” (Green & Troup, 1999, p.148)

Fernand Braudel from the Annales

In his 1966 book The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II Fernand Braudel goes into great length to convey the historical significance of geography upon cultural history. The first two hundred and thirty pages of his book set the scene for his readers geographically for the historiography that was being developed The first three chapters are: The Peninsulas: Mountains, Plateaux, and Plains; The Heart of the Mediterranean: Seas and Coasts; & Boundaries: The Greater Mediterranean. The last of which explores the effects of the mediterranean on the world which it interacted with and acted upon. “Braudel introduced a multi-layered historical chronology, and initiated a strong focus on quantitative history among the historians influenced by him.” (Green & Troup, 1999, p.87) Green and Troup go on to describe how “Braudel conceived time in a new way. For example, his famous phrase ‘the Mediterranean was 99 days long’ vividly evoked the effect of sea and horseback travel upon early modern communications. His spatial approach to the sea was equally novel; for Braudel, the Mediterranean extended as far north as the Baltic and eastward to India. Land and sea were inextricably connected….”(Green & Troup, 1999, p.89) The beautiful expressions provided in Braudel’s work remind us just how connected we are to the geography we inhabit and the sense of space we construct around ourselves.

Incorporating GIS as a Historical Methodology

This method is not an all encompassing approach to answering historical questions[9], and the tools available for research are limited in the types of questions they can answer to those that have some form of geographical component. With GIS we can see how humans organize their space, what do they do with their environment, and how their minds work in this organizational process. This works by delineating “space as a set of Cartesian coordinates with attributes attached to the identified location, a cartographic concept, rather than as relational space that maps interdependencies, a social concept.” (Bodenhamer, 2010, p.20) The Cartesian coordinate approach differs from our own relational experience with the world around us, and how we interpret and convey that experience.[10] When historians participate in this new digital form of geospatial mapping they contribute to a more shared understanding of reality[11].

GIS & Historical Scholarship

Ian Gregory and Paul Ell, in their book Historical GIS: Technologies, Methodologies and Scholarship, remain excitedly confident that “GIS has the potential to reinvigorate almost all aspects of historical geography, and indeed bring many historians who would not previously have regarded themselves as geographers into the fold.” (Gregory & Paul, 2007, p.1) If historians wish to engage with GIS tools then they will need to “not only learn the technical skills of GIS, but must also learn the academic skills of a geographer.” (Gregory & Paul, 2007, p.1) As mentioned previously, GIS allows users to shift the focus from a strictly historical narrative approach to a geospatial narrative in which questions can be asked in new, more computationally based, ways. Couclelis informs us that

“in applied geography- the geography that GIS is supposed to serve- the question of whether an object or field view is more correct, is neither a philosophical nor a theoretical issue, but largely an empirical one: how is the geographic world understood, categorized, and acted in by humans.” (Couclelis, p.70)

Scholarship leads the student down a field of study in an attempt to answer a question. This approach helps bring those answers to a visual life, but it requires carefully formed questions in conjunction with well structured, and accurate, data.

Data

This entire system of historical analysis requires two things, data and the knowledge of how to turn it into something useful. All of the data that the historian collects will require some structuring for it to be made into a historical work, and how the historian approaches the structuring “begs the philosophical question of the most appropriate conceptualization of the geographic world.” (Couclelis, p.65) How the data is structured[12] will help determine how the historical questions can be answered.

Ian Gregory has an interesting notion on how, in the future, historians may be able to address and visualize the dream of Lovejoy who was searching for The Great Chain of Being that linked ideas in their historical context and showed how they were viewed in different ways at different times. Gregory writes,

“in an ideal world, we would use spatial & temporal data to explore how a phenomenon has evolved over time, not by comparing two snapshots but by looking at continuous change. In doing so the aim is not to identify the story of how the process evolved but to use different places to explore the different ways in which the phenomenon could occur differently.” (Gregory, 2010, p.66)

Examples of GIS as historical methodology

The means of using GIS to further a historical understanding has been taking shape for some time now, and in this section I would like to take a look at some digital humanities endeavors that have taken form with GIS and that have a focus on history.

The first project is Pleiades. This project is great for those studying classical history, meaning particularly the Greek and Roman periods though they are expanding their gazetteer[13] into “Ancient Near Eastern, Byzantine, Celtic, and Early Medieval geography.” (Ancient World Mapping Center) Pleiades gives researchers the ability to “to use, create, and share historical geographic information about the ancient world in digital form.” (Ancient World Mapping Center) As of mid December 2015, they have just shy of 35,000 place names in their gazetteer. This project was created with the help of the Ancient World Mapping Center from the University of North Carolina, the Stoa Consortium, and the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World from New York University.

The second project comes from the University of Virginia and takes a look at “two American communities, one Northern and one Southern, from the time of John Brown’s Raid through the era of Reconstruction.” (Ayers, The Valley of the Shadow) It contains “original letters and diaries, newspapers and speeches, census and church records, left by men and women in Augusta County, Virginia, and Franklin County, Pennsylvania.” (Ayers, The Valley of the Shadow) The project seeks to give “voice to hundreds of individual people” by telling the “forgotten stories of life during the era of the [American] Civil War.” (Ayers, The Valley of the Shadow) Within this larger project is a section on battle maps that seeks to tell the stories of regiments from Augusta County, Va (Confederate) and Franklin County, Pa. (Union). The map allows for the display of additional layers including: grid and scale, putting a boundary line around Augusta and Franklin counties, displaying modern cities, highlighting historic towns, showing historic roads, resurrecting historic railroads, and highlighting major rivers. After selecting the various layers that needed to be added, the researcher can press play and watch the animated battles that ensue.

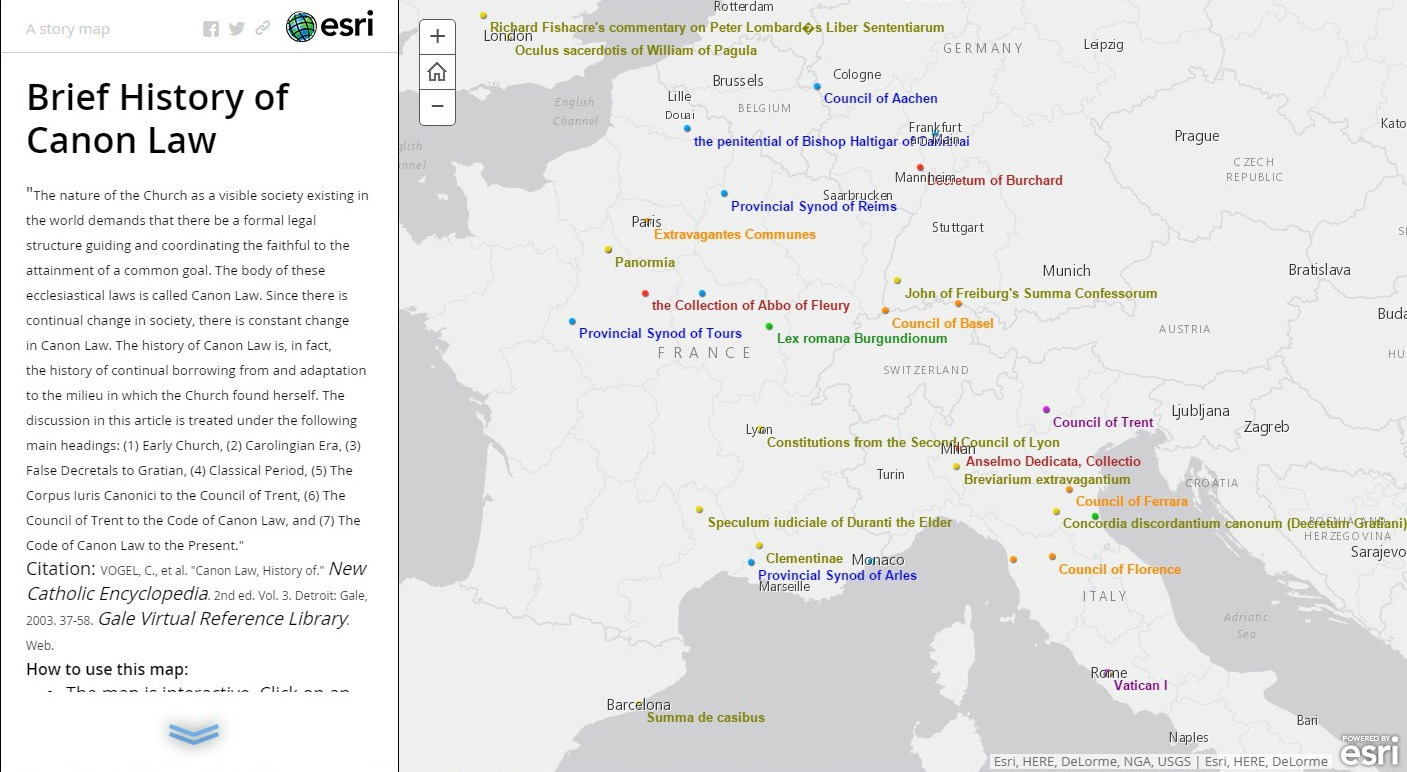

One project that I helped to create was the History of Canon Law map for the Religious Studies, Philosophy and Canon Law Library at the Catholic University of America. This was done in the online ArcGIS tool from ESRI . In order to create the content I created .csv files based on information found in the New Catholic Encyclopedia article “Canon Law, History of.” (Vogel et al., 2003) The value of the map is that it helps provide a geographical context for various councils and documents related to the history of canon law. The map breaks down the history of Canon Law into seven periods: Early Church, Carolingian Era, False Decretals To Gratian, Classical Period, The Corpus Iuris Canonici to the Council of Trent, The Council Of Trent To The Code Of Canon Law, and The 1917 Code Of Canon Law & The 1983 Code of Canon Law to the Present. Though the map is far from complete, it does provide the student of canon law the ability to obtain a different type of historical understanding than a traditional reading and analysis; it is also a nice overview for novices to the topic.

The final project is The History Engine which was created in the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of Richmond. I list this one last here because of it’s emphasis as more of a pedagogical tool for teaching undergraduate students of American History at the University of Richmond about the research and publication process, though it does appear that the creators are making their project available for use by faculty at other institutions. What is interesting is that while it is teaching students about research and publication, it displays their results in a geospatial and temporal context. The project itself was built using an API from Google Maps and incorporating the Timeline widget produced at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). I would like to encourage the reader to look at some of the other interesting history projects done by the Digital Scholarship Lab to see more great ideas.

Conclusion

Throughout this post it has been my goal to provide the reader with justification for the value of incorporating GIS tools into their arsenal of historical research methodologies. We have looked at the world in history through a spatial, temporal, and humanitarian lens. We have seen how a couple of approaches to history have paved the way for GIS as an approach to understanding historical questions. Lastly, we have seen the value that GIS can hold for historical scholarship, and a few examples thereof. When using this approach the historian will need to adapt some of their traditional practices, but the efforts will be worth the investment given the historians keen ability for breadth of research and analysis.

Bibliography

- Ancient World Mapping Center and Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. Pleiades.stoa.org. 2015 Available from http://pleiades.stoa.org/.

- Ayers, Edward L. 2010. Turning toward place, space, and time. In The spatial humanities: GIS and the future of humanities scholarship., eds. David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan and Trevor M. Harris, 1. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

- * ———. The valley of the shadow: Two communities in the american civil war- eastern theater of the civil war. [N.A.]Available from http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/VoS/MAPDEMO/Theater/TheTheater.html.

- * ———. The valley of the shadow: Two communities in the american civil war. in University of Virginia [database online]. [cited 12/17 2015]. Available from http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/.

- Bodenhamer, David J. 2010. The potential of spatial humanities. In The spatial humanities: GIS and the future of humanities scholarship., eds. David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan and Trevor M. Harris, 14. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

- Corrigan, John. 2010. Qualitative GIS and emergent semantics. In The spatial humanities: GIS and the future of humanities scholarship., eds. David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan and Trevor M. Harris, 76. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

- Couclelis, Helen. 1992. People manipulate objects (but cultivate fields): Beyond the raster-vector debate in GIS. In Theories and methods of spatio-temporal reasoning in geographic space / international conference GIS–from space to territory: Theories and methods of spatio-temporal reasoning, pisa, italy, september 1992, proceedings ., ed. International Conference GIS–From Space to Territory: Theories and Methods of Spatio-Temporal Reasoning (1992 : Pisa, Italy), 65. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- CUAphiltheoLIB. History of canon law. 2015 Available from http://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapJournal/index.html?appid=612a8448fbf34d598ed2a1d1b7f228bb.

- East, W. Gordon. 1967. The geography behind history. New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc.

- Green, Anna and Troup, Kathleen, ed. 1999. The houses of history: A critical reader in twentieth-century history and theory. New York: New York University Press.

- Gregory, Ian. 2010. Exploiting time and space: A challenge for GIS in the digital humanities. In The spatial humanities: GIS and the future of humanities scholarship., eds. David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan and Trevor M. Harris, 58. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

* Gregory, Ian N., and Paul S. Ell. 2007. Historical GIS: Technologies, methodologies and scholarship. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Lock, Gary. 2010. Representations of space and place in the humanities. In The spatial humanities : GIS and the future of humanities scholarship., eds. David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan and Trevor M. Harris, 89. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

- Sack, Robert David. 1986. Human territoriality : Its theory and history. London: Cambridge University Press.

- J. Scurry, SCDNR Land, Water and Conservation Division- National Estuarine Research Reserve System.What is GIS? Retrieved from http://www.nerrs.noaa.gov/doc/siteprofile/acebasin/html/gis_data/gisint2.htm (http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/virtual_disk_library/index.cgi/4928836/FID1596/html/gis_data/gisint2.htm)

- Vogel, C., H. Fuhrmann, C. Munier, L. E. Boyle, Sousa Costa De, P. Leisching, J. E. Lynch, and J. E. Lynch. 2003. Canon law, history of. In New catholic encyclopedia. 2nd ed. ed. Vol. 3, 37-58. Detroit: Gale, http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CCX3407701987&v=2.1&u=wash31575&it=r&p=GVRL&sw=w&asid=a828cd9e811f3af497a3d0503a3a4c78 .

* Yuan, May. 2010. Mapping text. In The spatial humanities: GIS and the future of humanities scholarship., eds. David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan and Trevor M. Harris, 109. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Notes

[1] Couclelis adds that “Territories too become objects when they need to be defended or fenced, but it is in their field- like, background form that they appear to have their most pervasive effects on human behavior.” By making territories an object a GIS user can establish boundaries by creating .kmz files and adding them into their GIS database. Couclelis, H. (1992). People manipulate objects (but cultivate fields): Beyond the raster-vector debate in GIS. In International Conference GIS–From Space to Territory: Theories and Methods of Spatio-Temporal Reasoning (1992 : Pisa, Italy) (Ed.), Theories and methods of spatio-temporal reasoning in geographic space / international conference GIS–from space to territory: Theories and methods of spatio-temporal reasoning, pisa, italy, september 1992, proceedings (pp. 65). New York: Springer-Verlag. p.73

[2] “Geography, at least in its physical aspect, provides a common denominator to all historical periods: more ancient than Methuselah, the land has witnessed and survived the advent of man and the ephemeral episodes of his purposive adventure.” East, W. Gordon. p.8

[3] In the Lord of The Rings by J.R. R. Tolkien, Gollum asks Bilbo this famous riddle regarding time: “This thing all things devours: Birds, beasts, trees, flowers; Gnaws iron, bites steel; Grinds hard stones to meal; Slays king, ruins town, And beats high mountain down.” From this we can glean that all the material world is fleeting and is subject to the passage of time. Nothing can escape from it that exists within it.

[4] “While time flows from an infinite past to an infinite future, space on the Earth’s surface is fundamentally finite.” Gregory, Ian. 2010. Exploiting time and space: A challenge for GIS in the digital humanities. In The spatial humanities: GIS and the future of humanities scholarship., eds. David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan and Trevor M. Harris, 58. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. p.61

[5] “physicists conceive of time as a fourth dimension that is inextricably linked to space.” Gregory, Ian. 2010. p.61

[6] “Time, like geography, can be disassembled analytically. Just as we differentiate between a more generalized space and a more localized place, so can we differentiate general processes from specific events. We live daily in places and events but we are parts of large spaces and processes we can perceive through efforts of disciplined inquiry. Just as a geographer relates places and space, so do historians relate event and process. Geography locates us on a physical and cultural landscape while history locates us in time. Joining the two kinds of analysis in a dynamic and subtle way to imagine both structure and activity, may help.” Ayers, Edward L. 2010. Turning toward place, space, and time. In The spatial humanities: GIS and the future of humanities scholarship., eds. David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan and Trevor M. Harris, 1. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. p.5-6

[7] W. Gordon East states that “The position of a Place at any time is affected, too, by the extent to which the known lands were populous or unsettled, civilized or barbarous.” East, W. Gordon. p.28

[8] “quantitative methods in history have encouraged us to extend our range of historical sources and topics, made possible more exact comparisons between societies over time, and focused our minds on specific historical problems and on ways in which we as historians construct our material.” Green, Anna and Troup, Kathleen, ed. 1999. p.148

[9] “The claim of geography to be heard in the councils of history rests on the firm basis that it alone studies comprehensively and scientifically, by its own methods and technique, the setting of human activity, and further, that the particular characteristics of this setting serve not only to localise but also to influence part at least of the action.” East, W. Gordon. p.2

[10] “Another challenge is whether or not Cartesian space can be adapted to incorporate a more humanistic sense and understanding of distance, direction, and position. While coordinate systems provide the quantitative basis for GIS, our own biological and cultural sat-navs work on qualitative relationships such as “next to,” “in front of,” “behind,” and “a little way past the supermarket.” Lock, Gary. 2010. Representations of space and place in the humanities. In The spatial humanities : GIS and the future of humanities scholarship., eds. David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan and Trevor M. Harris, 89. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. p.91-92

[11] “Maps are one, if not the, most effective form that records knowledge about geography where histories unfold and cultures develop and to serve as a shared reality.” Yuan, May. 2010. Mapping text. In The spatial humanities: GIS and the future of humanities scholarship., eds. David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan and Trevor M. Harris, 109. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. p.109

[12] As well as any philological arguments that need to be addressed as explanatory notes in the research.

[13] Gazetteers are “collections of place names with geographic locations (or footprints) and other information about these places.” Yuan, May. 2010. p.114